Building Software With AI Agents, For Real

Practical Guide to Agentic Engineering

It took me about an hour to get a working 3D configurator for a standard shipping container in front of a customer.

Normally that is a “we will get back to you in a few weeks” kind of request. In this case, the rules for the application were already written down in an ISO standard the model had seen before. Once I referenced the norm, I had a rough prototype running. It was not production ready. But they could click around, break it, complain about it, and suddenly we were iterating on something real instead of reviewing a pitch deck full of concepts.

The interesting part isn’t that it took an hour. It’s that the hour was possible at all. That only worked because I treated AI like a junior developer I could manage and feed with context, a plan, guardrails, and a “good enough for a demo” definition.

Everyone on the internet is busy arguing about whether AI will replace developers. That is the wrong question. The real shift is more operational and much more important.

Agentic development changes the economics of iteration, not which model you pick.

When you can show something tomorrow and refine it with real feedback, you make different product and engineering decisions.

If you have tried to build anything non-trivial with AI, you have probably felt it: things move fast at the start, then collapse around the last 20 percent. This article is about why that happens and how to change it.

TL;DR Agentic development is treating AI like a set of junior developers inside your repo, not a magic senior engineer. The limiting factor is the environment you build around them: context, plans, signals, and guardrails. That environment changes how fast you can iterate and how you structure work, which is why this matters.

In this piece, I will cover:

What agentic development looks like in practice.

Why it became practical once the Codex, Claude, and Gemini CLIs caught up.

How agentic workflows let one developer manage a small team of assistants on their behalf.

The skill ceiling people do not like to talk about.

The core pillars that keep agents from collapsing at 80 percent.

Think of this as a practical guide to agentic engineering: patterns that have worked for me after months of daily use, independent of any specific model.

What agentic development really is

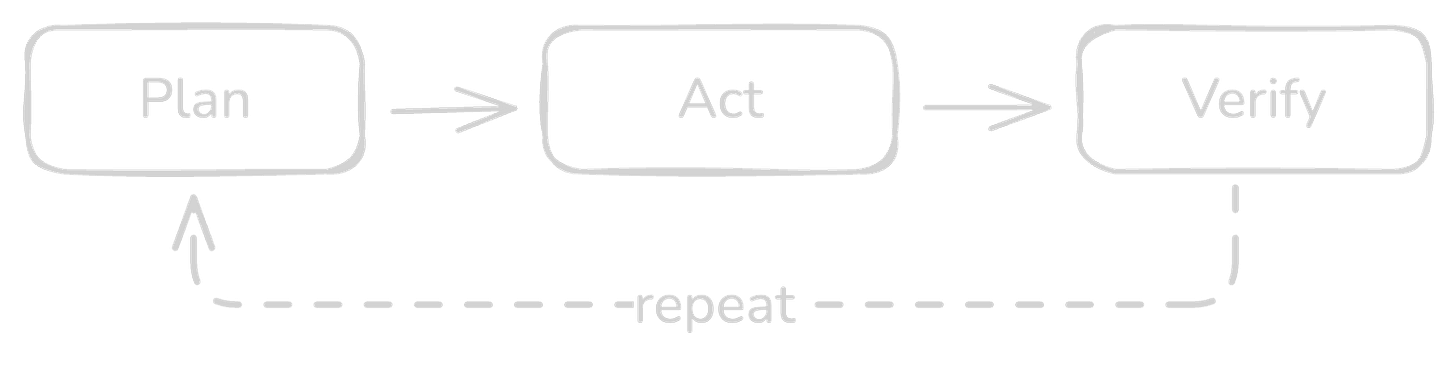

Agentic development is software engineering where you turn intentions into executable loops: plan, act, verify, repeat, inside a repository that stores context on purpose.

I will use “agentic development” and “agentic engineering” interchangeably here: development is the day-to-day practice, engineering is the discipline and structure behind it.

The closest analogy I have:

It feels like having junior developers on call all day: fast at implementation, dependent on you for context.

That can sound like a downgrade: why would you choose juniors when you could have seniors?

Because you do not get seniors on demand.

What you do get is a scalable amount of junior-level execution, as long as you provide:

a clear plan

enough context

guardrails and tools

and the discipline to review and steer

Your role shifts:

You stop being “the person who types all the code”.

You become the manager or product owner of your own project.

That comes with a simple constraint:

Agentic development has a ceiling, and it is set by you.

If you do not know what “done” looks like, the agent will not either. If your repo is undocumented and fragile, every session is a fresh onboarding.

Agents amplify skill. They do not replace it. “Agents can just figure it out.” They cannot. If you do not define plans, signals, and guardrails, you are not doing agentic development. You are pulling a slot machine and hoping to hit the jackpot.

Why prompts alone break: state and context

Most AI content stops at “paste your code into a browser and ask for refactors”. That frames it as a prompt problem. The real issues are state and context:

Work is stateful, prompts are not.

Why is this a workflow problem and not a “better prompt” problem?

Because prompting is a one-shot interaction.

state

retries and partial progress

verification

memory across sessions

If nothing in your system stores that state, in plans, task files, runbooks, or docs, you pay the same tax every time:

you rediscover the same facts

the model forgets them too

your “workflow” is just a series of one-off chats

Agentic development starts when you decide to stop paying that tax and treat state as something you design on purpose. If your system does not store state anywhere, you are not building workflows, you are starting a new conversation over and over again.

From feature work to context work

Agentic development flips the center of gravity: from features to context.

Traditional development is feature-oriented:

“Build the thing.”

Agentic development is context-oriented:

“Build the environment so assistants that start fresh each session can build the thing reliably.”

That sounds like overhead until you look at what changes:

You stop relying on “ask the lead engineer”.

You stop keeping setup quirks in your head.

You start encoding decisions where they belong, in the repo.

A new developer cloning a repo for the first time often hits problems that only exist on first setup. Someone gets called over. It gets fixed “just this once”. Nobody writes it down. A month later, someone else hits the same issue.

Agents are direct about this because every new session is a new developer with amnesia. If the repo is not self-contained, they stall. If you are tired of repeating yourself, you start writing runbooks.

It works like the pensieve from Harry Potter: Dumbledore pulling a memory out of his head and storing it in a bowl. Good agentic teams do that with context. They pull it out of brains and put it into the repository.

Loops, not guesses: “curl until green”

Consider a simple case: an endpoint is failing in staging.

Prompt-based pattern

you paste the stack trace into ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini

you get suggestions

you try a change

both you and the model forget what you already tried

you spiral

You are still guessing, only faster.

Agentic loop

Define the success signal:

“curl must return 200 with the expected JSON.”Give the agent tools:

run tests, run lints, build and restart services, inspect logs.Run the loop until the signal is green.

The curl is not just a command. It is the signal.

The loop is the agent.

This is the core difference: you are turning “try a thing” into “run a loop against reality until a clear condition is met”.

Once you see it this way, almost any debugging or repair workflow can be expressed as: define the signal, then loop against reality until the signal is green.

Why now: tooling made this practical

Models have been decent at code for a while, but the step change for day-to-day work came from tooling and harness.

What changed recently is not just that the models got better. It is ergonomics:

Terminal native workflows in the Codex, Claude, and Gemini CLIs that live next to your docs, tests and git history.

Standardised tool access through MCP servers (Model Context Protocol servers that expose tools and surfaces like browsers), so agents can drive real surfaces instead of guessing.

A reusable skills library that lets the agent see your runbooks and workflows everywhere without pasting them into every prompt.

Once agents live in your terminal, with your tools, you can build loops like the curl example. If they stay in a browser tab, they rarely make it past the demo stage.

Further reading on the tooling side:

Chrome MCP with Codex: Drive a real browser from your agent – how to let an agent drive a real browser.

Skills in Codex: A library for your workflows – how to turn repeatable workflows into reusable skills the agent can see everywhere.

Autonomy comes in levels

Can you say:

“Design a complex web app, implement it, deploy it,”

and hand that to an agent?

No. Not reliably.

You can think about it in levels:

Level 1: lint fixes and very small edits that are easy to verify.

Level 2: missing tests around existing behavior.

Level 3: code changes that run under a test suite and type checks.

Level 4: multi-step repair loops built around a clear signal such as the curl example.

Level 5: small orchestrated flows that follow a written plan and reuse context across steps, for example a small migration or internal tool flow that chains a few tasks together.

Your workflow becomes:

you groom

you plan

you verify

If you want meaningful autonomy, expect to write plans. A lot of plans. That is not a failure. That is the work.

The pillars: context, plans, signals, guardrails, tooling

This is the core of agentic engineering: agentic development becomes reliable when you treat it like engineering and build a harness.

1) Context architecture

Agentic workflows push context out of people’s heads and into the repo:

AGENTS.md as an entry point to rules, runbooks, and conventions.

Runbooks for common operations.

Docs that make setup self-contained.

Task files that store the current plan and state.

2) Plans as durable memory

Plans and task files are independent storage for context. Plans survive the session and act as shared memory. If a run crashes, hits token limit, or you swap models, point the next session at the file and it’s immediately caught up.

3) Signals and success criteria

Prompts tell the agent what to try. Signals tell it when to stop.

A signal is a machine checkable condition that separates “we are still working” from “this part is done”.

The interesting part is what happens when you bundle signals. A real task often looks like this from the agent’s point of view:

tests for the affected module are green

curl /health returns 200

a specific error log pattern no longer appears under load

When all of these are true, the task is done. When any of them are false, keep working.

That is how I think about plans in agentic development.

Plans consist of procedures and signals. Procedures are how to approach the task. Signals are what must be true before you move on. From the agent’s perspective, the set of signals is the spine of the plan. It does not have to invent what “good” looks like. It has a list of conditions it is trying to make true.

In my own setup this usually ends up as small task files that contain a description, a few procedure hints, and a list of signals. Walking that list once is a single turn of work for the agent.

4) Verification and guardrails

Treat the agent like a developer and send it through the same guardrails as everyone else:

Static checks and Language analyzers: catch type and semantic issues (tsc --noEmit, mypy/pyright, go vet/staticcheck)

Style checks and formatters: enforce style and hygiene (eslint/prettier, ruff/black, gofmt)

Dependency rules: enforce layer boundaries (depcruiser, import-linter for Python, ArchUnit for Java)

Tests: unit/integration (Jest snapshots, Go/Python golden files, JUnit approvals)

Run the same commands locally that CI will run. CI is the safety net, not the first place you discover issues.

These are the same gates you would use for any PR. Make the agent run them too.

5) Tooling and harness

Agents need a harness so they can run, see context, and stay safe.

Project docs as entry points: repo and sub-directory AGENTS.md files that point to the right commands and tools.

Validation: one command that runs the validation suite (tests, style, static checks, dependency rules), plus scoped variants for quick loops. The agent runs the same gate humans do.

Task and state files: a small task system with status snapshots and execution logs, so the next session resumes from recorded state instead of prompt memory.

Environment and adapters: declare how the project runs (for example Docker or local scripts) and provide wrappers to restart services, seed data, and instructions on how to hit HTTP/DB/browser surfaces.

Safety and logging: run in a restricted environment, keep secrets out of reach by default, and log command output for audit.

Skip the harness and you’re back to prompting and hoping.

The downside: the 80 percent problem

So where does this usually fall apart?

The last 20 percent is where things usually fall apart:

edge cases show up

integrations behave differently than expected

context drifts

success criteria were never written down

This is not a reason to avoid agents. It is a reason to add the missing engineering layer:

clear plans

explicit signals

verification loops

context that persists beyond the session

In demos you mostly see the 80 percent. The agent looks impressive and then quietly disappears when edge cases and real constraints show up. When you close the last 20 percent with plans, signals, and guardrails, you move from seeing agents to seeing agentic engineering.

What it unlocks in practice

Take the configurator from the intro. The only reason that hour of work was enough is that the behavior of the material lived in an ISO spec the agent could rely on once I mentioned it. The agent did not invent physics. It stitched together a UI and orchestrated code around rules that it was trained on.

The goal in that case was simple: give a customer something interactive they could click through and critique.

This is the real unlock:

You collapse the cost of iteration.

You make “show, then refine” cheap.

You change how you sell, prototype, and shape products.

On the other end of the spectrum, agents quietly handle boring work:

resolving lint errors

filling in missing tests

updating docs and runbooks

chasing down regressions with repeatable loops

You get leverage at both ends: faster experiments and less drag from maintenance.

How to start, for real (without betting the company)

You do not need a grand AI strategy. You can start with one repo.

Most teams try to start at level ten instead of level one. They hand a vague project to an agent and hope for the best. The steps below keep you at the low end of autonomy while you learn what works.

1. Pick a safe surface

Choose an internal tool, admin panel, or non-critical service you understand well.

2. Prepare the environment

Make sure lint, test, and type commands exist and are reliable.

Add a short AGENTS.md that explains what the repo does, how to run it, and where to find key docs.

Fix the obvious “new dev setup” traps you already know about.

3. Delegate low risk loops

Use an agent to propose a plan for lint fixes, missing tests, or a small refactor.

Let it execute under your guardrails while you review diffs and keep architectural judgment.

For one or two bugs, define a clear signal, like the curl loop, and let the agent drive fixes until the signal is green.

4. Encode what you learn

Turn the rough plan into a task file or runbook.

Update AGENTS.md with any new patterns.

Add a guardrail, test, check, or script so the same issue is cheaper next time.

That is enough to move from demos to a small, real agentic workflow.

Why this actually matters

Agentic development matters because it shifts software engineering up a layer. This is what building software with AI agents, for real, looks like in practice`.

Programming languages become second-level abstractions. The primary skills become:

designing workflows

encoding context in the repo

managing levels of autonomy

verifying outcomes through signals

AI is not replacing developers any time soon. But developers and teams who learn to manage agents inside well prepared environments will outpace those who do not. The leverage adds up. The gap widens, quietly at first, then obviously.

If you found this useful, you can subscribe to get future practitioner-first pieces on agentic development and real-world AI workflows.

If you want help rolling these patterns into your own teams, reach me at marco@heftiweb.ch.

For shorter, more frequent notes and experiments, I’m on X as [@marcohefti](https://x.com/marcohefti).